Conjuring Magic with Black Girls in Oakland

Zakiya Scott

Describe yourself in three words.

Brave, listener, visionary.

Tell us about yourself.

I'm a Southern Black queer writer and editor, youth advocate, and communications strategist who believes in the transformative power of storytelling to uproot racist systems and change culture. My journalistic practice is a love of language, a pirouette with Black Queer Feminist (BQF) praxis, and a forever connection to Black womxn and girls who channel generational struggle into generational healing, wisdom, and truth.

With roots in North Carolina’s community newspapers and radio programs, I moved to Oakland to fuse my passion for writing and storytelling with my desire to realize more justice and empathy as a communications and media intern at the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights. I went on to work at Fenton, where I provided media relations, messaging and strategic communications support to grassroots nonprofits and foundations within the firm’s social justice practice.

Most recently, I worked at Blackbird to further the communications needs and strategies of the Movement for Black Lives—a coalition of more than 50 organizations committed to fighting for Black liberation and community, institutional, cultural, and systems transformation that centers and values the lives of all Black people. Now, I merge media, organizing, and journalism to develop and execute communication strategies for folx who are committed to making bold interventions to advance Black freedom, justice, and liberation.

Tell us about the work that you are doing with CSS.

The long-term plan is to build out a story-based strategy (SBS) curriculum that centers Black girls and womxn in their own learning, political education, and media-making. The curriculum will culminate in Conjure the Magic: An Embodied Pedagogy for Our Rebellion (Vol. 1), a 4-part series with narrative interventions and tools for Black girls and womxn. The tools and interventions will be designed to support us to understand our experiences, and create and share our stories, perspectives, and analysis in our communities.

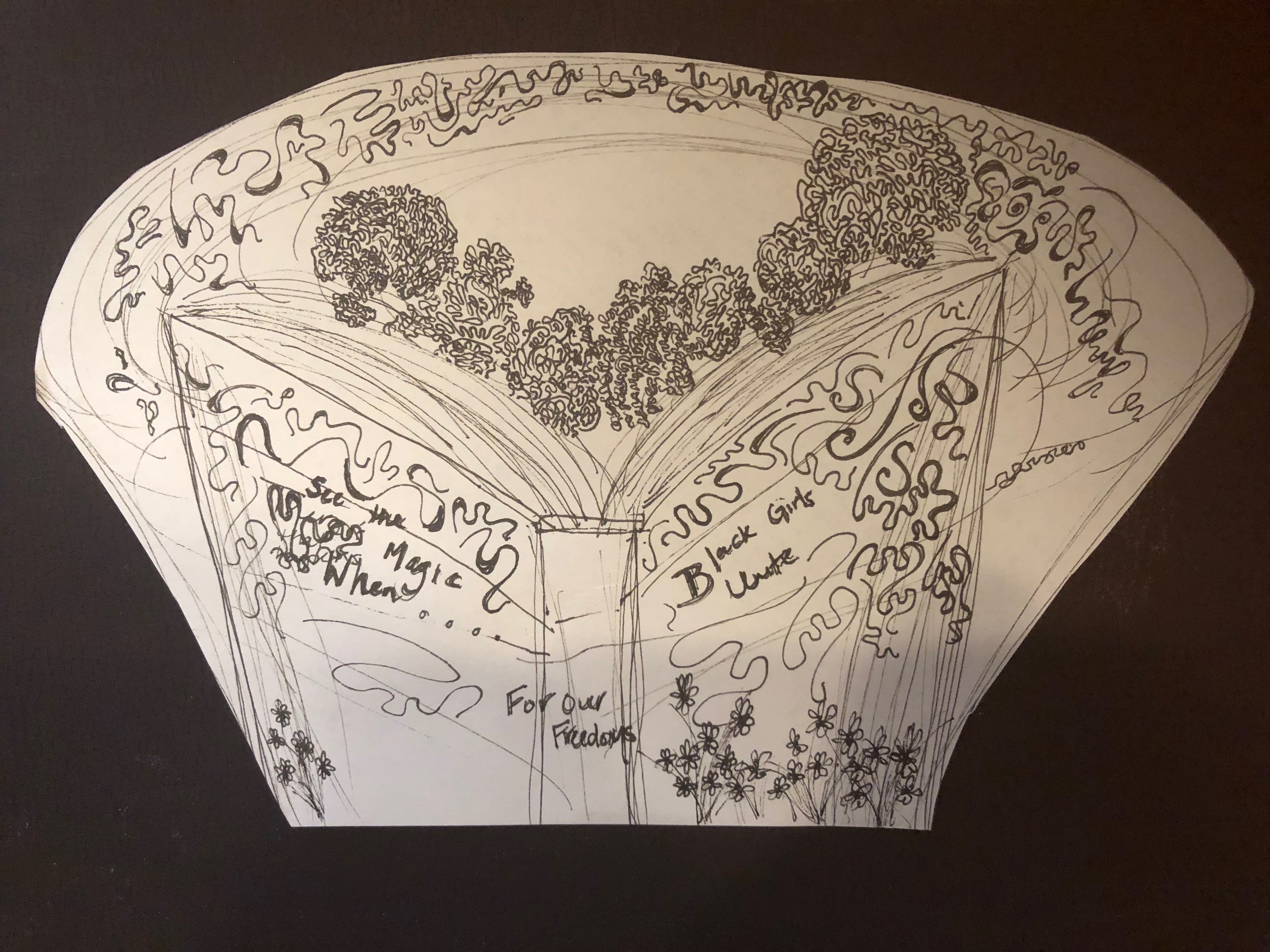

Secondly, I’m gauging community interest in the creation of the Magic Book Bus: A Book Fair for Black Girls, a traveling learning space. The idea is that we have a physical space to hold Black girls’ imagination, nourish reading appetites, learn from and with each other, and spark story creation. To get there, I’m creating bookmarks to illustrate both what’s in store for the first book fair and the magic that truly happens when Black girls and womxn unite for our liberation.

Explain to us why you are doing this work.

During the 2018-2019 school year, and a time of rampant gentrification and utter decimation of public education in Oakland, OUSD School Board Members voted to close Roots International, a middle school in East Oakland. The decision to close at the end of the school year, was spearheaded by the school's principal and announced to the parent and school community by way of a pre-recorded audio message just before school let out for the December holiday.

Before the closure of Roots International was announced, Cecelia Jordan, the schools restorative practices coordinator, invited me in to a weekly, restorative space called Black Girl Magic for the 8th grade girls at Roots. Black Girl Magic made space for the daily fights between them to end and for their rebellion to be acknowledged and loved. It gave time to process the top-down decision to close Roots and up to 23 other schools, and to channel student energy toward creativity during the Oakland teacher's strike.

There, I began to understand what it might look like to build a more healed and shared understanding of our history, identity, politics, and how stories surround and propel our lives. In spite of Roots’ closure, I am still committed to support Black girls as they continue their education journey through middle school and high school, and beyond graduation to college. I believe that the work is to bring Black girls and womxn together to revisit ancestral stories and develop and articulate new stories where we love ourselves, protect each other, and have the tools we need to lead a rebellion toward a future beyond survival. All of that is in service of reimagining what Black liberation can be.

Share how folks can get involved with your work or see your work’s final product.

Email editor@ourmovement.media to stay informed on the fundraiser for the curriculum, Conjure the Magic: An Embodied Pedagogy for Our Rebellion (Vol. 1) and for the Magic Book Bus: A Book Fair for Black Girls. In the meantime, you can support the Book Fair directly right here.

How would you describe Story-based Strategy (SBS) to someone who has never heard about it?

If storytelling and revolutionary organizing go hand-in-hand, then Story-based Strategy is the delicate, yet intentional handshake. While Story-based strategy is also an analytical framework, it’s really a practice of freedom: it enables a moment of pause to confront feelings of fear, of harm, of loss, and spurs us to courage, bravery, and truth in the moments we need it most. It illuminates the stories we put out in the world to build power and shift behavior, and the stories we tell ourselves and live with as we light and sustain a clear path forward. It restores our sense of connection to each other and our sense of humanity in times when empathy wavers. It’s a toolbox that is energizing and mind expanding. Story-based Strategy illuminates pockets of mutual liberation—where listeners and storytellers, learners and teachers, stories and strategies for freedom meet.

How did SBS affect your work on the project?

For Conjure the Magic: An Embodied Pedagogy for Our Rebellion (Vol. 1), the building of the curriculum leaned heavily on ways to apply SBS tools like Battle of the Story and Fairy Tales to introduce young folx to narrative development and campaign strategy.

Unsure of where to start, I began with traditional communications approaches I’ve used in the past with youth organizers. When crafting a message or a story that centers oneself, I’ve often used the VPSA model: shared Values, introduce the Problem we face as it relates to the Values, connect to a unique Solution we’re offering, and end with Actions that lead to our vision of the future. However, after developing my Cornerstones once, going back and revising them, and applying a Narrative Power Media Analysis (NPMA), the proven “VPSA” formula was not as applicable to the complex and intersectional nature of the project. SBS, like organizing and advocacy work, is a non-linear process; and I too, needed to embrace a non-linear approach in spite of my familiarity and comfort with the VPSA structure in my work. That’s when I turned to the Drama Triangle and experimented with Fairy Tales as both an introduction to drama triangles, the Battle of the Story, and narrative power media analysis, and to the overall curriculum meant to center the experiences of Black girls.

For the Magic Book Bus: A Book Fair for Black Girls I went through many iterations of how to make this happen. First, I wanted to create a report card for students and families to fill out and submit back to their principals to demonstrate power and to intervene on who should be listening to whom. This led to conversations about imagination spaces—particularly what Black girls and their families imagine a school can be and what interventions would assert and advocate for this space. Still, without being in conversation and in SBS practice with the girls themselves, I recognized this intervention was rooted in my limited perspective.

I turned to a NPMA, beginning with Their Story, to research and better understand what current stories were being told about Black womxn in society and Black girls in Oakland schools:

Their story

conflict: the school board vs. experts in Oakland community (activists who often attend school board meetings)

characters: students, teachers, school board members, activists, parents

imagery: “stage” where school board members sit, gymnasium where everyone else is

foreshadow: school board doesn’t listen; protesting at the school board meetings will get us to the world we want

underlying assumptions: protesting at school board meetings will achieve the change we want; there’s an achievement “gap” at “low-performing schools,” “the system is failing us all” and as such attendance and enrollment is the biggest issue; “numbers” (and money) = “children” (and hearts/young minds)

heroes: District administrators, especially principals

villains: advocates, activists

victims: students at closing schools

It was already clear that we needed new narratives and more power to expand our vision beyond the criminalization of Black girls in schools.

My analysis led me to prioritize three things for Black girls and our healing in the new narratives we need:

an expression of feeling(s) like care, joy, sadness, anger, disgust, fear with and for ourselves, each other and the world,

the creation of more space for our unique personalities to keep us afloat when the opposition is committed to drowning us out, and

to increase our ability to live in the present while we make the future, now.

"Represent the Future" mural for Lakeview Library. Art directed by @emagn1. Oakland’s first ever mural art painted on a city owned building. Located at 550 El Embarcadero, Oakland, CA 94610.

All of this pointed me to literacy. Not just reading and writing, but narrative and storytelling literacy. What then would it look like if we were collectively committed to the creative development of Black girls as readers, writers and storytellers who’s stories will indeed shape our shared future? Part of landing on the bookmark itself is to present an offering to Black learning communities and to gauge interest in a book fair—both are rooted in the intention to do not for, but with our people.

How was working on this project, using SBS, different from your work without SBS?

Without SBS, it is easy for me to get stuck in the analysis phase. Using SBS helped me get to specific and realistic points of intervention—at points of consumption and assumption—that can both expand conversation and provide tangible resources for the communities I am apart of. SBS reminds me that the point of healing-informed and culturally relevant curriculum isn’t just for it to live on a page or on a shelf, but to be embodied and brought to life in the streets and under the sun.

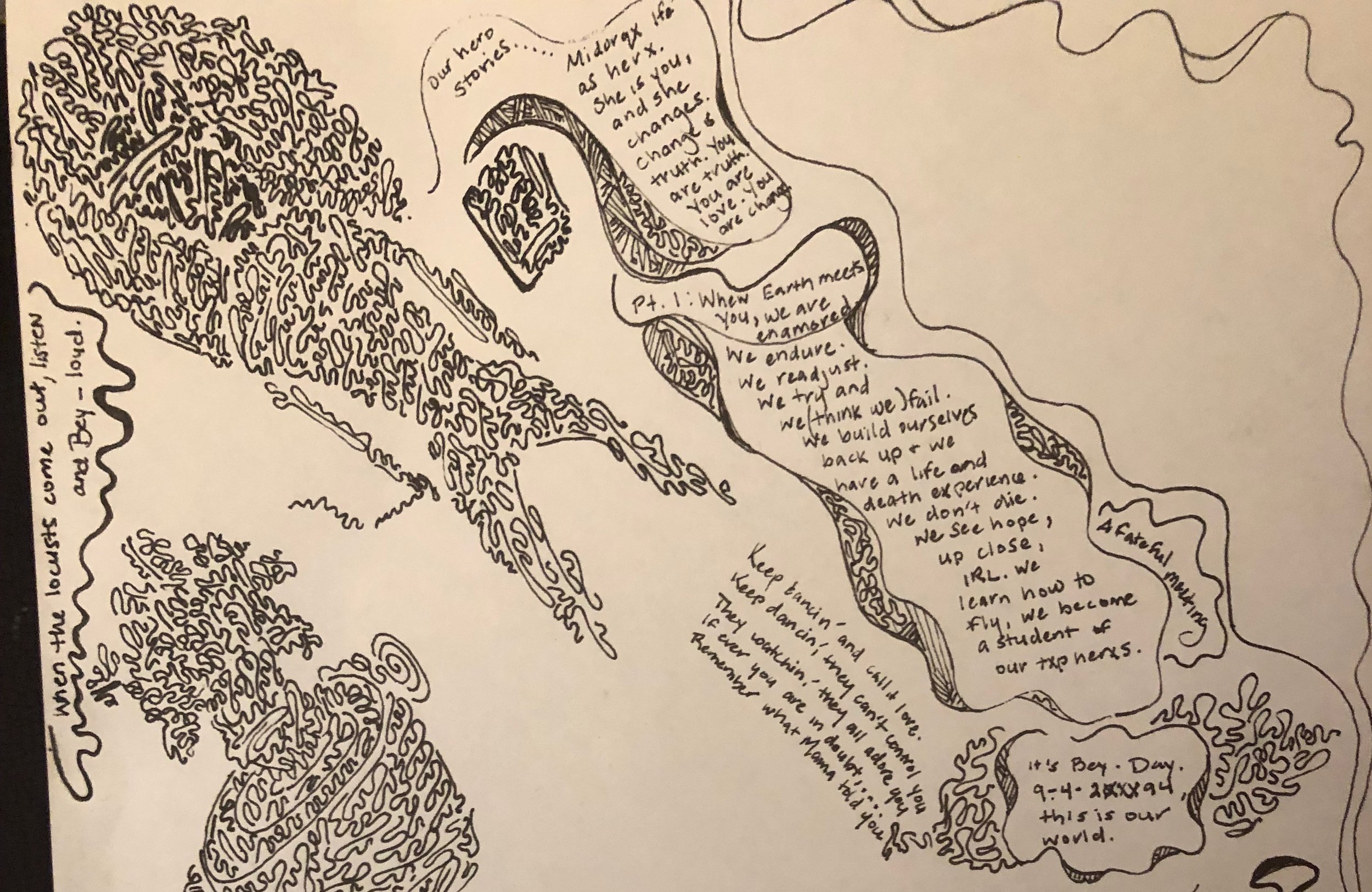

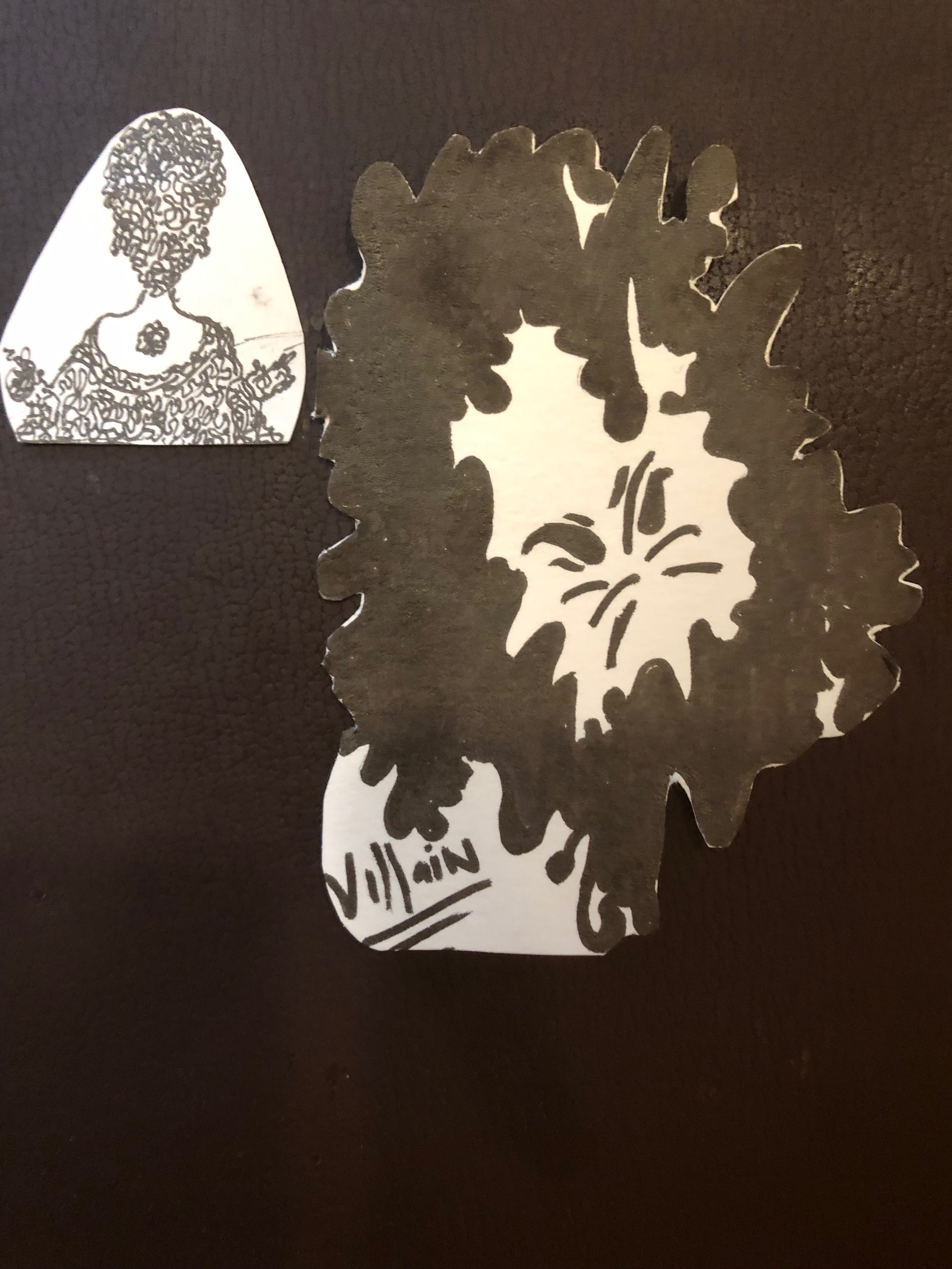

Early sketches for animations to be included in Conjure the Magic: An Embodied Pedagogy for Our Rebellion (Vol. 1). By Zakiya.

Through SBS, an intervention is more than an execution of a pre-preconceived idea. Instead, interventions become a collaborative process, a way to bring other people into practicing narrative strategy so that thinking and acting from the level of story becomes ingrained in our minds and hearts.

If you could have another iteration of your work, how would it have changed?

I would have loved to bring more young people into this experiment of story and resilience-based organizing. If I could bend time and stretch my capacity, I would’ve made these tools more accessible to the Roots community during the fight for their neighborhood school, adapting them to be playful and powerful tools to bring the narratives they wanted to the forefront.

Do you think SBS will change how you relate to future work in collaboration with others? How? And why?

Yes! Listen to Ari Lennox’s outro on New Apartment, when she says, “… And then I realized, oh my god, I need people!” The Fellowship allowed me to get my SBS reps in and connect with folx who also have a SBS practice. As an independent communications consultant, working in isolation is too-often the norm. Through a continued SBS practice with others, I know that we can hone and activate creative ideas, while being lovingly held in communities of accountability and learning.